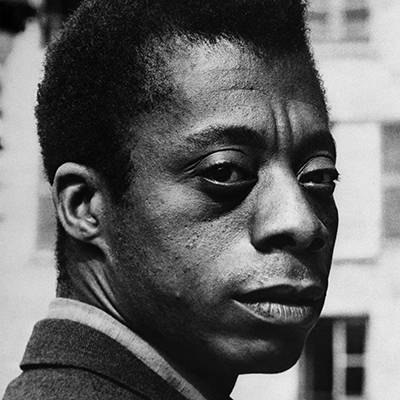

The Confessions of James Baldwin

I cannot remember precisely when I first encountered James Baldwin’s writing — sometime in early high school, perhaps — but I remember that it was not a quote, or even one of his novels, that ushered him into my life.

It was actually a brief poem:

Lord,

when you send the rain,

think about it, please,

a little?

Do

not get carried away

by the sound of falling water,

the marvelous light

on the falling water.

I

am beneath that water.

It falls with great force

and the light

Blinds

me to the light.[1]

I was completely enamored of this pocket-sized poem, especially with the word “Untitled” looming over the page in a bold, arresting font. Poems without titles always felt more like confessions, words that could not be contained but that burst from the mind into the world. Baldwin’s untitled confession had fallen into my lap, and it left me uncertain about my gaze. And yet I felt compelled to carry it around with me, tucked in the notes app of my phone.

When I moved to Berkeley last fall, Baldwin’s novel Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953) was the first book I picked up. I had finished Giovanni’s Room a few months earlier. I remember reading the final twenty pages of the novel in my childhood bedroom, in the complete silence of the night, and feeling for one of the few times in my life that I had been fundamentally changed by something. I pondered this feeling for a long period of time, wanting an answer to why Baldwin’s writing — not just the content, but his language — struck my soul in a way so few writers could.

The Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive’s recent screening of two James Baldwin documentaries — Sedat Pakay’s James Baldwin: From Another Place (1973) and the newly restored I Heard it Through the Grapevine by Dick Fontaine and Pat Harley (1982) — gave me an opportunity to revisit this feeling. The event was held in late February 2024, and featured an introduction by Stephen Best, director of UC Berkeley’s Townsend Center for the Humanities and professor of English and film & media.

The short film From Another Place, which documents Baldwin’s self-exile in Istanbul, Turkey (1961-71), lays the foundation for what is portrayed in I Heard it Through the Grapevine. From Another Place begins with Baldwin meditating on his departure from the States. He refers to American power as ubiquitous, even when his own body and mind are removed from the country. And yet, he notes, “still it’s true that one sees it better from a distance.” The idea of "seeing" unfolds in a multitude of ways in the film's opening scene. The audience watches Baldwin as he goes through the motions of his morning: he puts on a robe; smokes a cigarette; flutters out of frame, then back in again — while the camera hardly moves. Over these images, a voiceover plays. Baldwin engages with the audience vocally, but visually he is preoccupied. In a clear, definitive moment that sets the mood for the rest of the film, Baldwin puts out his cigarette, stands so that the camera can capture his face, and bares his truth to the viewer: “I consider myself to be a kind of witness, I suppose.”

In his introduction to the two documentaries, Stephen Best drew attention to Baldwin’s self-identification in this scene, emphasizing Baldwin’s rejection of serving as “the next Black spokesperson” during the post-civil rights era. Instead, Baldwin embraced the role of “witness,” preferring to use his pen as his tool, as he expressed in From Another Place. However, Baldwin did not just bear witness to the world from a distance. As the camera lingers on the lone figure of the writer, his silhouette backlit by a bedroom window looking out into the expansive topography of Istanbul, it becomes clear that Baldwin also bore witness to conditions of the self within the world.

Baldwin’s meditations on exile, American power, and occupying the role of witness all come to fruition in I Heard it Through the Grapevine, which chronicles his return to the South in the 1980s after his almost decade-long absence. Structured like a road trip and interwoven with archival footage, the documentary follows Baldwin as he goes from place to place — Birmingham, Alabama to St. Augustine, Florida — reconnecting with past civil rights activists with whom he worked in the 1960s. The storyline is supplemented by a present-day conversation between James Baldwin and his brother, David Baldwin, as he recounts this journey. Sometimes Baldwin is at the forefront; other times, he is in the periphery, bearing witness to those who tell their stories.

Despite the complexity of the timelines, the documentary establishes a lucidness which melds the present with the past and vice versa, enhancing the discourse on change and the question of progress that is at the center of the film. As Baldwin goes from state to state, revisiting tragedies such as the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing and the ‘64 murder of civil rights activists James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman by the KKK and a Neshoba County sheriff, the film offers a comparative perspective. Baldwin and other activists recount their past experiences while simultaneously sharing their present reflections. The documentary and its interviewees maintain a reflective honesty when contemplating what had (or had not) changed in the two decades since the civil rights era.

The film, however, never spirals into pure pessimism. When reflecting twenty years later on Freedom Day and on the Black residents of Dallas County who rallied together and lined up to register to vote, only to be met with electoral malpractice and brutal state violence, James Baldwin says: “I don’t want to say ‘well, nothing has changed,’ something is always changing, but the town has not changed. The spirit has not changed at all. It is as it was when we were there almost twenty years ago.” Moments later the documentary shifts to present-day New Orleans, Louisiana, which had at the time of Baldwin’s return the highest number of Black elected officials in the union. Despite this, as activist Oretha Castle points out, the state was petitioning to build juvenile detention centers for Black youth. Baldwin echoes this same frustration: “Everything has been changed on the surface, and nothing else has been touched.”

In establishing the absence of deep-rooted, structural change, I Heard It Through the Grapevine sets out to widen the viewfinder through which present-day audiences perceive post-civil rights progress. The documentary positions the lack of progress as a product of state conditions during the civil rights movement, which actively worked to undermine full social and economic equality for Black Americans. Castle explains that when she heard President Lyndon B. Johnson’s appropriation of the phrase “we shall overcome” in his 1965 voting rights speech, she knew that this “hypocritical effort on [LBJ’s] part to gain cheap publicity” meant that the civil rights movement would be “a long, long, protracted struggle.” As the documentary emphasized, the doctrine of white supremacy is so fundamentally ingrained in the interests of the United States that it systematically works against true, restorative change. As Baldwin echoes when talking about the 1965 Selma marches, “we had fought so hard to vote, only to enter the system and realize there’s nothing to vote for.”

Both documentaries screened at BAMPFA were made towards the end of Baldwin’s life. As Best noted in his introduction, only recently has Baldwin’s writing begun to regain popularity. Towards the end of his life, he was ostracized, neglected, and publicly shamed by both his generation and the following one. Precisely the critical stance Baldwin took on change in I Heard It Through the Grapevine, others used against him and his writing. For example, in a 1998 piece published in the New York Times, Michael Anderson wrote, “Little wonder [Baldwin] lost his audience: America did what Baldwin could not — it moved forward.”[2] Baldwin argued precisely that America had not moved forward — or at least not to the degree so many claimed — and so society abandoned him as a result. As we sat in BAMPFA’s Osher Theater almost four decades later, it felt salient to ask why only after the writer’s death did society feel comfortable engaging with his work. This is not new; history is full of contemporary silences, and many wait until the dust has settled, until the harm has been done and all the responsible players have passed on, to utter their first words. Very few, like Baldwin, speak out when their words are most needed, and when they have much to lose. In the closing lines of I Heard It Through the Grapevine, Baldwin leaves the audience with a final note: “I expect nothing from them; I finally expect everything from us.” May we strive, then, to live up to Baldwin’s request and bear witness not to the aftermath, but to the moment.

In the closing scene of I Heard It Through the Grapevine, Baldwin walks along the beach with Nigerian author Chinua Achebe, his voice echoing over a shot of waves crashing along the shore. “There is no refuge from confession but in suicide,” he says. Returning to Baldwin’s work after the screening of these two documentaries, I began to finally grasp why his writing exercised such a profound effect on me. Baldwin has a way of building up momentum through language so that everything he writes feels like a steady march towards some confession. On that site of confession, where the sky opens up and the light breaks through and the truth rains down, despite bewilderment one understands the need for Baldwin’s words. It is a need not just for what those words signify, but for the act of speaking them. In the final moments of I Heard It Through the Grapevine, I understood that for Baldwin, confession was a requirement of having lived life as a witness.

In his concluding line, Baldwin warns that as time marches forward, the Western world nears the day that it can no longer hide from confession. His warning becomes visually embodied in the crashing waves, which hit the shore in a steady, unending act of repetition. As the camera moves away from Baldwin and Achebe in the final moments, and lingers instead on the rhythmic crashing of the waves, the documentary makes it clear that Baldwin’s prophecy lives beyond Baldwin himself. Forty years later, in BAMPFA’s Osher Theater, this still rings true: confession is inevitable.

[1] https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/88936/untitled-56fd7727ab2dd

[2] https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/joseph-vogel-baldwin-piece/#:~:text=Some%20ascribe%20this%20 abrupt%20 decline,insecure%20role%20in%20black%20America.