On Not Taking History for Granted

October 3, 2020 marked 150 years since the UC Regents approved the admission of women to UC Berkeley as undergraduate students. To celebrate this important milestone, the departments across campus have undertaken a major history project, 150 Years of Women at Berkeley, to preserve written and oral histories of women on campus.

In conjunction with the archival project, several departments have hosted events to explore the history of women at Berkeley and to discuss ongoing challenges in creating an equitable and diverse campus. On April 21, 2021, the Townsend Center joined in the commemoration with the event “Ongoing Revolution: Reflections on Gendered Struggles and Feminist Scholarship in the Humanities.” Four faculty members from different humanities departments joined with Catherine Gallagher, Professor Emerita in the Department of English, to discuss the history of women at Berkeley and the ongoing challenges in creating a diverse, representative faculty.

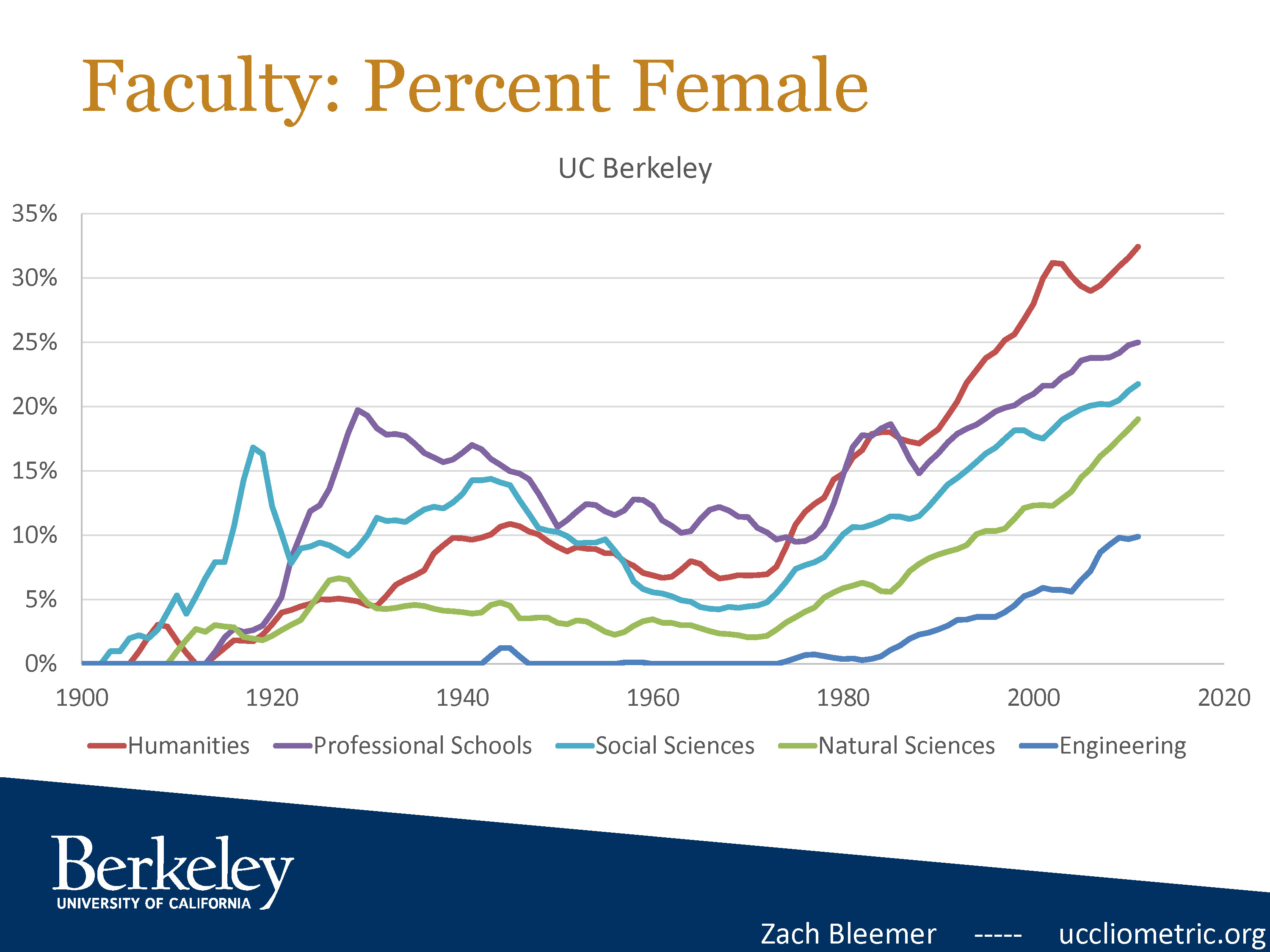

Gallagher introduced the event with several statistics on the growth of female faculty by department since 1900. In the late 1970s, female faculty members challenged the University’s discriminatory hiring and promotion practices and used the federal and state legislature to force the University to adopt more inclusive hiring practices, including affirmative action. Since then, the number of female faculty members has steadily risen, although percentages still remain quite low in fields such as Engineering (where women faculty represent only 10 percent of the faculty) and the natural sciences (where women represent just over 15 percent). The humanities employ the most women, with roughly 33 percent. Some departments within the humanities, such as Spanish & Portguese, are evenly split between men and women, while women even make up a majority of the faculty in the History of Art department. Despite major increases between 1900 and the present, the statistics show there is still much to be achieved in the representation of women on campus.

Mary Ann Smart, Professor of Music, presented a brief early history of women in the Music department. When she arrived at Berkeley in the 1990s, she was told that Bonnie Wade had become the first female faculty member in Music in 1975. However, Smart’s research into course catalogues shows women faculty were teaching as early as 1947. Women in the Music department were most often music performance lecturers, teaching piano and other instruments, rather than professors of musicology. Madi Bacon, an early music lecturer who worked with the Berkeley Extension program and designed several courses on music theory, complained, “I don’t think that women have been particularly successful on this campus. . . . At UC Berkeley, I was never given tenure. After eight years, I was still a lecturer.” Although the Music department was open to hiring women, it provided little in the way of career advancement and restricted what they could teach. Another early woman in the department, Winifred Bliss Howe, who worked as an assistant professor of harmony for 15 years, was a gifted composer with numerous musical accomplishments. She was, for instance, a founding composer and publicist for the Carmel Bach Festival. Despite her musical accomplishments, her biography in Berkeley’s Music Library focuses primarily on her romantic relationship with a fellow music professor, Ernest Bloch. Smart’s research into the history of women in the Music department shows that discrimination against women extended beyond unfair hiring practices and led to underappreciation of women’s talents and accomplishments in academia. Francine Masiello, Professor Emerita of Comparative Literature and Spanish & Portuguese, shared her personal experiences joining the faculty in 1977, a moment when women across departments were fighting for fair hiring practices, equal pay, maternity leave, and other rights. Masiello was hired not only for her expertise in Latin American literature, but because she was willing to teach an upper-division course on the image of women in literature. At that time, several advanced graduate students in the Comparative Literature department had insisted that the department offer undergraduate courses on women in literature and prevailed in their demand after much persistence. The first group of undergraduates to participate in the course became the first Women's Studies majors at Berkeley. Through her involvement with the course, Masiello became connected to other women faculty on campus and beyond; she quickly felt the support of women mentors working in various fields, from psychology to statistics. With several colleagues in the Spanish department, Masiello created the Seminar on Feminism and Culture in Latin America, which eventually co-authored a book, Women, Culture, and Politics in Latin America, in 1992. Her collaboration on this project taught her the value of archival research and influenced her later scholarship.

Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Professor of History of Art, has had close ties to Berkeley her whole life. Her mother worked as a secretary in several departments and, growing up, Grisby knew many women on the staff. She later attended Berkeley as an undergraduate and then returned as a professor. When Grigsby started as an undergraduate in 1960, women were severely underrepresented in the History of Art and Art Practice department and subject to anti-feminist practices. The archives of course catalogues show that in 1965, only two of the department’s 27 faculty members were women; Sventlana Alpers and Guitty Azarpy had their names listed as “Mrs. Alpers” and “Miss Azarpy." Even in 1970, Professor Alpers was listed under “Svetlana Alpers (Mrs. Paul J).” Much has changed since then — women now outnumbermen in the History of Art department, and courses that take a feminist approach to art history are regularly offered. Yet Grigsby cautions against taking these advancements for granted. Many of her undergraduate students saw the truth of her warning when a female professor retired and was replaced by a highly respected male modernist art historian who taught entire courses without mentioning a single female artist. Though women have made significant progress since 1965, Grigsby says she remains outraged that women are still a minority on the Berkeley faculty, especially in the STEM fields, and she wants her students to recognize that the feminist struggle in academia is ongoing. As much as the 150 Years of Women at Berkeley History Project is a celebration of accomplishments, it is, Grigsby noted, a record of pain, outrage, and injustice.

Sophie Volpp, Professor of East Asian Languages & Cultures and Comparative Literature, discussed the ways her field of specialization, pre-modern Chinese literature, has changed over the decades since she began her PhD. In the early years of Volpp’s studies, pre-modern Chinese scholarship focused heavily on manuscripts and dating. However, pioneering archival work by women in the field challenged commonly accepted notions of the traditional Chinese woman and brought gender into the field. Volpp has contributed to making women more visible in pre-modern China by translating the works of female writers for publication in anthologies. Like Masiello, Volpp felt great support from fellow women faculty early on in her career. When she arrived on campus, she was assigned a woman faculty mentor. At events for women faculty, other scholars encouraged Volpp to apply for fellowships and guided her through applications. Volpp’s experiences show how academic disciplines have slowly opened not only to include more women faculty, but to give a voice to women of the past through research that challenges traditional views of gender difference.

Although the 150 Years of Women at Berkeley History Project focuses primarily on the accomplishments and experiences of women doing academic scholarship, Gallagher and the panelists ended with a message about the importance of undergraduate and graduate students in creating a more equal, diverse campus. Gallagher stressed that changes in the gender composition of the faculty came through student pressure, rather than initiatives from leadership in the university. Grigsby noted that, especially among graduate students, there is a desire to see more Latinx, Black, queer, and trans faculty members across departments. For Volpp, women even just a few years older than she were a great inspiration and aid in her early career, and she noted the desire among current graduate students for the university to hire people of color who can also serve as mentors.

Significant progress has been made since the 1970s, when female faculty and graduate students fought for more equal hiring practices. In addition to hiring significantly more women faculty members, the campus has created classes that include more women's voices. Scholarship in the humanities has expanded to challenge traditional ideas about women. Yet it is important to remember that there still remains much work to be done in expanding the diversity of UC Berkeley’s faculty — and the gains made cannot be taken for granted.