Colette, Misfit Sexualities, Registers, and Contexts

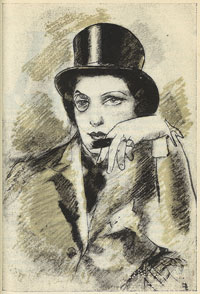

From an illustrated 1934 edition

of Collette’s "Ces Plaisirs…"

Illustrations by Clément Servean.

In the book I published in 2006, Never Say I: Sexuality and the First Person in Colette, Gide, and Proust, I investigated the role of a number of literary figures in the uneven establishment of what have become the dominant social forms for modern lesbian and gay identities in France. I was interested in the construction of certain literary and social practices that enabled particular versions of those identities to be elaborated in the first person (both in public life and in literary texts). The first person itself, it seemed to me, could in its various enactments be thought of as a social form or artifact that is collectively produced, sustained, and ratified. Figures like André Gide and Colette were particularly interesting to me because of the way at various moments in their life they understood (implicitly or explicitly) that bringing one’s sexuality and sexual life into the public eye—enacting a sexuality or a sexual identity— could count as a component of a literary career (at least in France at that time).

Sexuality is complicated; the labels and categories we have for it rarely do justice to the complexity of any given individual’s sexual life. Some of Colette’s most interesting writing explores how difficult it is to grasp the complexity of sexuality, to represent certain features of its enactment, how difficult it is for most people to articulate an account that captures all that their sexuality encompasses. Her 1932 volume, Ces plaisirs… [These pleasures…] is particularly rich in this regard. I wrote a bit about it at the end of Never Say I, and it has turned out to be the starting place of my next book as well. (The illustrations for this article are taken from a 1934 edition of Ces plaisirs…. Colette would later revise this text and publish the new version under the title The Pure and the Impure.) In my book-in-progress (Someone: The Pragmatics of Misfit Sexualities in Recent French Literature) my goal is to think about what we might call misfit relationships to established gay and lesbian identities. That is to say, I am interested in the conceptualization (or the difficulty in conceptualizing) and the representation (or the resistance to representation) of same-sex sexualities that do not manage to correspond to mainstream gay and lesbian identities. The non-correspondence between these misfit same-sex sexualities and mainstream ones may have to do with an odd temporal relation to those mainstream identities, the feeling of being somehow before or after them, or with questions of geographical location (the perpetuation of older sexual forms in non-metropolitan areas for instance, forms whose durability is precisely linked to their location in regions where time, so to speak, moves more slowly). It may have to do with a discordance between gender identity and sexual identity. It may have to do with the non-permanence or non-exclusivity of same-sex practices within a given person’s sexual history, to the way those practices are distributed between public and private areas (or conscious and unconscious areas) of that person’s being, and so on.

One of the central hypotheses of Someone is that certain misfit sexualities exist in language and culture without ever being explicitly talked about or explicitly laid claim to. Talking about them may be nearly impossible given the way a particular language and culture work, but these sexualities nonetheless leave other kinds of traces, more pragmatic than semantic. We might, for instance, know in some practical kind of way that there are important differences between the sexualities of different individuals without having the words to say what those differences are. We might make distinctions in practical dealings with people around sexuality about which we are inarticulate. In short, we know more about sexuality in practice than we can actually say. What would it mean for an author to write about a phenomenon about which one knows more than one can say, to write about aspects of it that seems inarticulable? Such writing becomes a space that is meant to activate the implicit pragmatic cultural knowledge of a reader (should the reader have the practical knowledge in question available for activation) through which inarticulate differences are apprehended. Such writing might thus serve to call attention to the myriad ways we draw on inarticulate bits of cultural knowledge in order to act in the world, to understand other people, to interact successfully with them.

From an illustrated 1934 edition

of Collette’s "Ces Plaisirs…"

Illustrations by Clément Servean

During most of Ces plaisirs…, Colette writes about her younger self talking to people about their sexual experiences during the French Belle Époque. Colette clearly understands that these conversations involve all kinds of rhetorical moves that make implicit reference to her own sexuality, yet she writes as if both her own sexuality and her own framework for understanding sexuality should be easily intelligible to her reader. She shows a particular interest in sexual misfits, in “certain privileged creatures and their steadiness in what seems like an impossible balancing pose, and especially in the diversity and steadfastness of that part of their sensuality that was for them a point of honor. Not just a point of honor, but a kind of poetry….” She writes, in short, as if only the subjects of her inquiry—those acrobats of the sensual world, miraculously balanced at a point in time or in cultural space, the difficult poetry of whose balancing act she interprets for us—require the attentive reading she provides.

And yet there is also something acrobatic about the position she constructs for herself; her own intelligibility, the frameworks and concepts she invokes in presenting minority sexual cultures and misfit sexual subjects have seemed to most readers anything but self-evident.Her chosen register, we could say, is in some way too idiosyncratic, not widely available, too unofficial.

Registers are (in the linguistic anthropologist Michael Silverstein’s formulation) “context-appropriate alternate ways of ‘saying the same thing’ such as are seen in so-called ‘speech levels.’” At stake in the discourse on sexuality in Ces plaisirs… is the negotiation of a shared sense of what are “context-appropriate” ways of talking about misfit sexualities, but also the negotiation of what constitutes sexuality, its fit or misfit, what constitutes “the same thing.” In speech or writing about sexuality, just as in other forms of speech or writing, registers allow for different kinds of social positioning. One assumes (and not always correctly) that one’s audience recognizes the import of a selection (not necessarily a conscious one) from a contrasting set of possibilities encompassed in a given set of registers—or one hopes one’s audience appreciates the import of an improvisation that adds a new register to a set of otherwise well-known ones. There is something tantalizingly unrecognizable about what Colette does with register in Ces plaisirs…, something about Colette’s sexuality that extends to her way of understanding the sexuality of others that is hard to characterize semantically or taxonomically. It is hard to know to what sexual culture she belongs, to what point in time her sexuality might be attached.

Interesting conceptual conundrums arise from a situation like this, regarding, for instance, assumptions we implicitly or explicitly make regarding the kinds of concepts that are immanent in any given cultural universe—including our own—and the extent to which those concepts are shared, the extent to which they circulate, the patterns of their distribution. There are also questions regarding how literary works become meaningful because of the ways they can be suspended in a variety of contexts, how they take their meanings from our ability to call those contexts into being as we read them.

Ces plaisirs…, like most of the literary texts from the French tradition that I take up in my study, wants to call a strange sort of attention to sexualities that escape dominant or even emergent categories of apprehension.Texts that undertake this kind of work develop particular resources to encourage us to pay a glancing form of attention to those sexualities that resist representation by the way they fail to conform to the categories that normally enable us to notice, to speak about, to name, kinds of sexuality. They point to sexualities or to aspects of sexuality that can’t exactly be referred to.

What does it mean to say that non-mainstream, unofficial, misfit sexual forms and cultures almost necessarily have a heavily pragmatic or indexical (a diminished semantic) existence? Their transmission, perpetuation, and survival depend on the transmission and circulation of both the frames of reference that grant them whatever modest intelligibility they have and the implicit codes or rules or genres of interaction that make them up. One of the most intriguing features of this project for me has been watching literary authors collectively develop techniques to deal with the problem of how language can invoke practical but non-referential understandings of misfit sexualities. Sometimes people assume too easily that pragmatic characteristics of language (those parts of language that link an utterance to the moment or the scene of its production, to its context) fade or even disappear from written texts as they move out through time. But working on the authors I study in Someone has made it clear to me that the pragmatic or indexical side of language does not simply disappear within written discourse. The indexical functions of signs in written texts, the semiotic features which are involved in putting these texts to use, in reusing them, continue to register non-referential or “misfit” contents. Grappling with a difficult work like Colette’s Ces plaisirs… can help us experience the ongoing implication of written texts (and of our selves) in the social world. As Pierre Bourdieu once wrote, “It is because we are implicated in the world that there is implicit content in what we think and say about it.”

Michael Lucey is Professor of French and Comparative Literature at UC Berkeley.

This article can be found in the February/March 2012 newsletter.