Genealogy of a Book

I recently had occasion to read several dozen applications for a dissertation year fellowship and thus came to realize that most scholars (not only the students but their advisors who have written letters for them) conceive of humanistic scholarship as involving a two-part process, research and the “writing up” of the research.

Having just finished a book myself I’ve been led thus to reflect on my own scholarship and how differently it proceeds—for good or ill— from this research/writing model, for I frequently (and especially in the case of this book) find the writing itself, which is begun from the very beginning of the project and deeply intertwined with the reading, the process of discovery which leads finally to the thesis and argument of the book, just as the book is nearing completion. After the formation of an initial hypothesis, research, thesis-formation, and writing are, for me, not only simultaneous but one process.

In the space so generously afforded me here, I’ll exemplify this with a sort of genealogy of the thesis of my just completed Socrates and the Fat Rabbis. The initial hypothesis that brought this project of reading, thinking, and writing into being was a thought that not only did the Sophists have much more to offer and to teach us than usually thought but that in fact their thinking had been much more accepted than that of Plato for hundreds of years, if not more. The book was going to be a defense of Sophism and an account of how it could serve us intellectually today. This was a fine hypothesis, indeed, so fine that as I fairly quickly discovered, there wasn’t much new about it at all, but it did have the virtue of sending me to study Greek intensively (for the second time in my life but this time it “took”) so that I could read the works (Plato’s and the Sophists’) that I wanted to write about. In the next stage of its life, the book morphed, then, into the following, a book called Exit Plato: Rhetoric, Politics, and Sex in the Ancient City. In describing the project then, I wrote: “My desire here is to recover currents of thought in the living, breathing Athens around Plato, not, I hasten to add, as a social historian but, indeed, as an intellectual historian and then to rewrite important aspects of early Christian and Jewish intellectual history with a view towards shifting our perceptions of the understanding of ‘truth’ within those traditions. Many (I warrant most) Athenian thinkers thought very different thoughts than Plato did. They have at least as much claim to be the ‘consummate expression’ of Greece as does the philosopher.” The project was then, and for much of its adolescence an antiprotreptic to philosophy (Protreptic is a kind of rhetoric that seeks to convert someone to a way of thinking and a way of life), and I continued then in my expose, “Much of Plato’s writing, I will suggest, is an extended protreptic for the particular form of political life that he promoted and much of that protreptic, I will suggest, was directed against the most important of his rival teachers, Isocrates. The fact that our own generally held narratives of the history of Greek thought match almost to a word Plato’s portrayal of it are a testimony to the enormous skill of Plato’s propaganda, much more than they are witness to the actual character of his opponents, sophists, rhetors, and Isocrates (who denies both titles, as does Plato).” For me, then, Plato was only the type of an alienated (and rather right wing) intellectual (a kind of Roger Scruton, perhaps): “I propose, then, in the first part of my book a revisionist reading of Plato as a politician, as a political actor. Plato and Isocrates can be understood as respectively two models for a contemporary imagination of political life (political in the broadest sense of the life of a citizen in a democracy). Plato represents the lonely, alienated intellectual (or religious) whose commitment to and knowledge of an absolute truth (philosophical) prevents him or her from participating in a pluralistic, democratic polity—this much is explicit in Plato— while Isocrates represents a household based, relativistic epistemology (rhetorical) of life within such a polity. At some level (which needs, nevertheless, to be seriously complicated, and will be in this project), the first could be said to represent a certain early Christian (monastic) ideal, while the latter is more like the rabbinic ideal. Both, I will assert, have their promises and their pitfalls. But I will argue that the victory of the Platonic model of truth and its denigration of the rhetorical tradition have had devastating effects on our religious and political lives.” It will be noted, moreover, that at this stage in my thinking and writing on this project, I was still (oddly) holding fast to old contrasts between Jews and Christians, mapped now, however, not onto a Semitic authenticity, Platonic incursion but rather onto a Jewish rhetoricity and a Christian Platonism.

In this form and under this title, following a year of intensive further study of Greek and Greek philosophy supported by the Bridging grant of the Committee on Research and the Townsend Center, the project received major support from the Ford Foundation. It had mostly been written at this time along the lines of the above paragraph.With the aforementioned support of the Ford Foundation, however, I embarked upon my sabbatical year to (hopefully) complete the book. But the book transformed itself during that year, and that is the main story of this little article. First of all, I became increasingly troubled by the fact that all of the critique that I was mobilizing against Socrates came from Plato’s works themselves. Since my thesis was predicated on Socrates being the unequivocal hero of Plato, this left me in a pickle. Secondly, the more I thought about the Talmud, the less it seemed to me that it was a dialogical text, as usually claimed (not least by me), and the more it seemed a practice of “monological dialogue,” not at all unlike Plato. Although these two considerations rather upset my applecart, I let them perform that office, and the thesis became transformed, once more.

By the Spring of 2007, when I was happily ensconced at King’s College, Cambridge, the renewed thesis began to come together. Having dispensed with the idea that Plato’s dialogues are dialogical, and then, reluctantly made the same admission with respect to my (much more) beloved Talmud, it still seemed as if something was not done (aside from the fact that I would have had a rather grim book, if at all, at that pass.) But then a penny dropped (almost literally—I am trying to get at the contingency of all this): Mark Jordan (supported strongly by Virginia Burrus) had protested my reading of the Symposium quite early in my project, suggesting that the real crux of the text was not Diotima’s speech but Alcibiades’s. At first this didn’t answer at all to my intuitions, neither about Plato nor about the Symposium, but now suddenly those ideas, dormant in my mind for two years, sprouted. Coming back to Bakhtin, once again, taking very seriously (but not solemnly) his ideas about the dialogism of a text not being in the dialogue between characters but between elements of the text itself, I felt that both the Diotima and the Alcibiades could be read as crucial in creating that which Bakhtin himself calls “a crude contradiction.” In a parallel time-frame I was thinking more and more about the grotesque elements of the Talmud and especially about narratives of obese Rabbis with penises of absolutely stupendous proportions. The thesis was once more beginning to come together. Rather than a contrast between Plato and the Talmud, a kind of convergence of literary strategy emerged, and both could be read under the sign of Menippean Satire, an ancient genre most sharply recognized by the fact that it is of intellectuals and about themselves, an assertion of their commitment to their own practices as well as a satirical reflection on the ultimate failure of those same practices to make the world (or even themselves) right even according to their own lights. Both achieve these ends by surprisingly similar means, with the most incongruous of concatenations of the “serious” [spoudaios] and the comical [geloion]. In the Plato this is carried out via the encounter between the gravity of the philosophical dialectic and the sometimes grotesque portrayal of Socrates as silenus and in the Talmud through the un/matching of profoundly important dialectics on the correct interpretation of the Torah with equally or even more grotesque portrayals of rabbinic heroes.

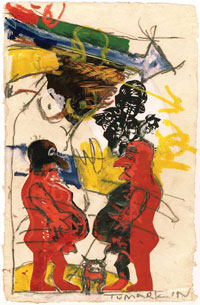

It took, however, another chance discovery by my wife, Chava Boyarin, for it all to come together (such as it is) into a coherent text. She found a piece of art by the leading Israeli artist, Yig’al Tumarkin that is an actual illustration of the narrative of the fat Rabbis with their grotesque genitals. When I showed this image to the distinguished Cambridge Greek scholar, Malcolm Schofield, he, quite innocent of the talmudic passage itself, immediately exclaimed: “Jewish silenoi”! Upon seeing the art work and, even more upon receiving permission to use it on the cover and as frontispiece for my book, a title ensued, Socrates and the Fat Rabbis, and a governing trope (that had been struggling to break forth from a much thinner text and title), the grotesque disproportion of male bodies as a figure for the celebrated indecorousness of discourse; the illformedness of the bodies and the texts as a marker of the final inability of truth to be found, or even of a final despair in the very enterprise of searching for it, one that does not, however, seek to end or even discredit the practice, whether the truth sought is the truth of philosophy or of Torah. The book suddenly felt done, but it was literally only in the last weeks of its writing that both thesis and form finally emerged.

Daniel Boyarin is a Senior Faculty member of the Townsend Fellows this academic year. In the fall semester he presented part of his current research project, "Socrates and the Fat Rabbis". He will deliver the Faculty Research Lecture on April 1, and offered the following remarks on the genesis of his forthcoming book.

This article can be found in the April/May 2008 newsletter.