Reclaiming the Aura: B.B. King and the Limits of Music Notation

Years ago, when I was a graduate student at Harvard, I heard B.B. King present a lecture. It was the most amazing lecture on music I had ever experienced. Experienced, rather than heard, because what he demonstrated about sounds forced me to question my values about listening and challenged me to form new paradigms about how to hear. I was a contemporary composer being educated in the Western classical tradition, and a B.B. King lecture was not really part-and-parcel of my doctoral curriculum. To be sure, composers like Ravel and Gershwin were influenced by the popular music of their time; and composers today find themselves delineated into countless hyphenated niches—avant-garde, neo-classical, post-modern. In the university system, though, composition students generally analyze more Beethoven than blues. An education in music composition, in the strictly classical sense, equips the student with the tools of the Western canon and generally emphasizes an understanding of where one’s budding voice fits in the scheme of things—the historical responsibility of writing music after the eras of your Mozarts and Prokofievs. Yet, for all the compositional theory and score-analysis, all the performances given and attended, there was something missing, which seeing B.B. King illuminated for me. His lecture revealed an aspect of music that I had, up to that point, never recognized despite all my classical training.

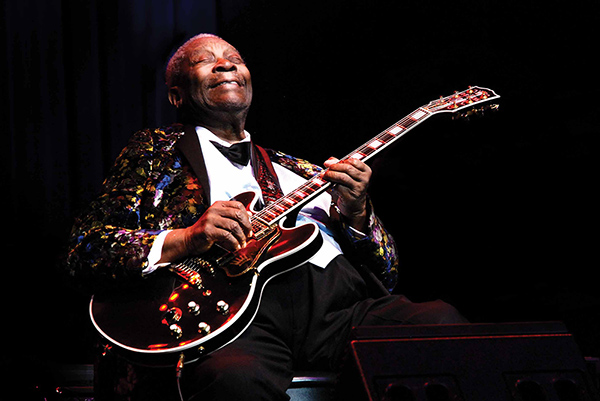

It was a snowy evening in Cambridge, the last week before winter break. The band played for a full ten minutes while we waited for King to come onstage. Of course, when he did finally walk into the hall, he immediately received a standing ovation. He went over to his guitar and sat down, the band stopped to let him talk, and with that characteristic smile full of wisdom, he delivered to us some important lessons on musical authenticity. “I go around the country,” he began, “…and many guitar players want to play for me. So, I listen. One thing I don’t understand is, why they want to sound like A or B. I tell them, if I wanted A or B, I can GET A or B!”

Having grown up emulating Jimi Hendrix, I identified with that ambition to sound like your heroes—like anyone who has ever been inspired by someone else. Yet if King had resolved to only imitate his mentor, T-Bone Walker, his reputation likely never would have extended beyond the borders of Mississippi.

The theme of finding your own voice carried through to the highlight of the evening, when King demonstrated how he improvises. First, having his band vamp on a standard twelve-bar blues, King showed he could play the “right” notes and proceeded to solo for twelve bars. The notes he played were restricted to the appropriate scale and harmonies of the twelve-bar progression—everything in the right key, nothing out of place, very straightforward. It sounded pretty cool, relaxed but still creative. Then he said, “I can play the same notes, but I can turn it ON!” When someone like B.B. King turns it on, you feel it! What he played was some of the most amazing live guitar I have ever heard. The notes came alive!

It is hard to explain exactly how King “turned it on.” The notes he played were roughly the same, but with personality, bending over and under the “right” notes of the scale. The rhythms were sharper, with an energy his first solo lacked. There were subtle technical differences, certainly, more creative use of space, sharper attacks, more sensuous slides, but the underlying motivation was a change in the man himself: King was expressing something, telling us a story from his heart.

Everyone watching felt the same shift in expression, the same change in temperature. It was almost like in the first solo King was reciting text and in the second solo he was preaching a sermon. The experience challenged and seemed to be in contradiction to how I was being trained as a classical musician—I mean, how do you transcribe someone’s personality?

One of the things you are taught in classical training is to analyze the works of the masters by looking at their scores. We look at how masters like Beethoven and Brahms created intricate musical structures by splicing, elongating, and inverting themes—using the same notes in different permutations. A venerable respect for the written score is developed through this kind of analysis, and we begin to think that the answer to all the genius and magic of the masters’ music is in the score. Moreover, the culture of performance practice surrounding classical music exists to preserve the intentionality of the composer by being faithful to the score, meaning that a work of classical music is transportable: many people can perform the work, and the identity of the work outlives (or survives) any one interpretation or performer. This is the special means by which the auras of classical composers have been transmitted through the ages—through a physical reproduction, from generation to generation. The written score also has the consequence of privileging certain aspects of sound, because it is limited in the amount of information it can convey. In general, only those frequencies which are playable on the piano are considered usable material in classical music, to the extent they are notate-able in the Western system. In this way, the notated relationships between notes in a work of music, expressed in a score, emanate its essence.

B.B. King’s demonstration taught me that the key to tracing his genius was beyond the scope of thinking about music in this purely textual way. We felt his genius by tracing his aura, his personality. Since the blues is an aural tradition, we can’t depend upon faithfulness to a score to judge accuracy of intention or identity. When B.B. King sings “How Blue Can You Get?” I am not tracking how faithful he is being to songwriter Leonard Feather’s intentions; I am listening for how the song is a vehicle for King.

Recordings have helped aural traditions not only preserve the legacy of a performance but also shape the listening values of our contemporary culture. Audio recordings preserve and transmit B.B. King’s voice, the tone of his guitar, and the intricacies of his playing, aspects that classical notation fails to transmit. In effect, audio recordings are more democratic and truthful than written scores. Recordings also aid in our emotional investment in our favorite artists. Through repeated listenings to our favorite recordings, we learn the subtle cues of the specific voice and sounds of our favorite artists, and we develop a kind of relationship with them, an empathic exchange. We begin to feel like we know them, that they are delivering some comforting truth that relates to our lives. And specific songs become inextricably linked with a specific artist. It is true that aficionados of classical music have their favorite recordings, and they too can revel in the aura of their favorite performers; but the traditional hierarchy privileging the intentionality of the composer still holds true. Symphonic recordings, for example, are still catalogued by composer. Ergo, the larger revolution is the effect technology has had on non-notated music.

My intention is not to elevate the merits of one genre over another. As a classical composer, I am deeply indebted to the legacy of classical music, and the paradigms of listening that it proposes have shaped me tremendously. I am also a lover of all kinds of rock and pop music. My main aim here has to do with the imperious nature of the paradigms of classical music in academia. For many, classical music holds a privileged place in terms of pedagogy and prestige, to the extent that non-classical cultures of music are evaluated through the lens of classical music. Many times, this means that special microtonal (frequencies between the notes of the piano), timbral, or rhythmic features of a musical culture that is non-classical are filtered out of consideration. The effort to capture an aural tradition in this way runs the risk of misrepresenting it completely. My hope in calling attention to what is special about listening to the blues is that we might begin to make a space to honor differences in paradigms of listening, rather than trying to force all listenings to be subsets of one dominant paradigm. Listening is too diverse and beautiful to remain undemocratic in this day and age.

The aura of a great blues artist transcends the cultural jadedness we have accumulated over a history of art reproduced through mechanical means. The B.B. Kings of the world reconnect us to a soulfulness that is necessarily transmitted through live performance. The uniqueness of a blues performance in time and place also reminds us that life is ephemeral, and beautiful for that; because it is ever changing, we must embrace the now.

Associate Professor of Music Ken Ueno is a composer, vocalist, improviser, and cross-disciplinary artist. He was a 2012-13 Townsend Fellow and is a member of the Center's Music & Sound Initiative. A longer version of this article was originally published in “Reclaiming the Aura: B.B.King in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” in Blues - Philosophy for Everyone: Thinking Deep About Feeling Low (John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2011).

This article can be found in the September/October 2013 newsletter.