Sugarcane Fields Forever

It was a ritual of childhood. I would clamor for a piece of sugarcane and my Uncle Richard would finally oblige, stopping the jeep, leaping athletically from the driver’s seat, striding to the edge of the cane field, lifting his steel machete, and effortlessly slicing off a yard of bright green cane. He would then turn back toward the jeep, thoughtfully whittling the edges of the cane as he went, so that I could begin to chew the pulp right away. I would receive this bounty, not without a certain reverence, and begin to eat as we continued to roll deliriously down the dusty white road through the fields, enclosed by two translucent green walls and a narrow strip of fervent blue sky. The cane was as sweet and heavy as the Jamaican sunlight. But I would all too soon suck the stalk dry, and there was nothing left to do but spit out the pulp.

It was only later and in the course of a different sort of consumption that I began to understand the oppressive weight of the history crystallized in the cane. Jamaica is a small island, one hundred and fifty miles long and fifty miles wide, lushly tropical, ringed by white sand beaches and crowned by misty blue peaks, a world unto itself, surrounded by the Caribbean sea. And yet the waves of what Karl Marx called the “world-historical” have washed up on those shores for nearly half a millennium, and its exports, from sugar to popular song, have had an oddly outsized role in the making of the modern world.

Jamaica was ‘discovered’ in 1494 by Christopher Columbus, settled by Spaniards, and eventually annexed by the British Empire. Its induction into Britain’s New World of commodity production and global trade networks spelled the end of the island’s indigenous old world — the ‘land of wood and waters’ of the Taino Indians. The Taino, decimated by disease and displacement, were replaced by enslaved West Africans, imported by the British to work the sugar plantations that helped fuel the economic engines of Empire and transform Jamaica into what Jane Jacobs has termed a “supply region” — a largely monocultural agrarian economy run almost entirely for the benefit of someplace else. The descendents of these unwilling exiles (and to a far lesser extent, their British masters) still populate Jamaica, along with Chinese, East Indians, and Syrians who were brought to the island as indentured laborers to fill the labor gap opened by the final abolition of slavery and emancipation in 1838. That same year, just as Queen Victoria ascended the throne, the British East India Company led the charge into China to preserve their vastly lucrative, if illicit, franchise as purveyors of raw opium to the Qing Empire. Jamaican sugar sweetened Indian infusions sipped from cups of Chinese porcelain, financed by a triangular trade in narcotics; from the ritual text of afternoon tea, we can read the oceanic circulation of goods and labor that built a new global economy.

This history of racial domination and economic exploitation was brought home to me as a child by the reggae records we brought back to the U.S. from family trips to the island. Jamaica gained its independence in 1962, at the high tide of postwar decolonization, becoming one of the nearly fifty post-colonial nation-states to emerge from the ruins of the Second World War.

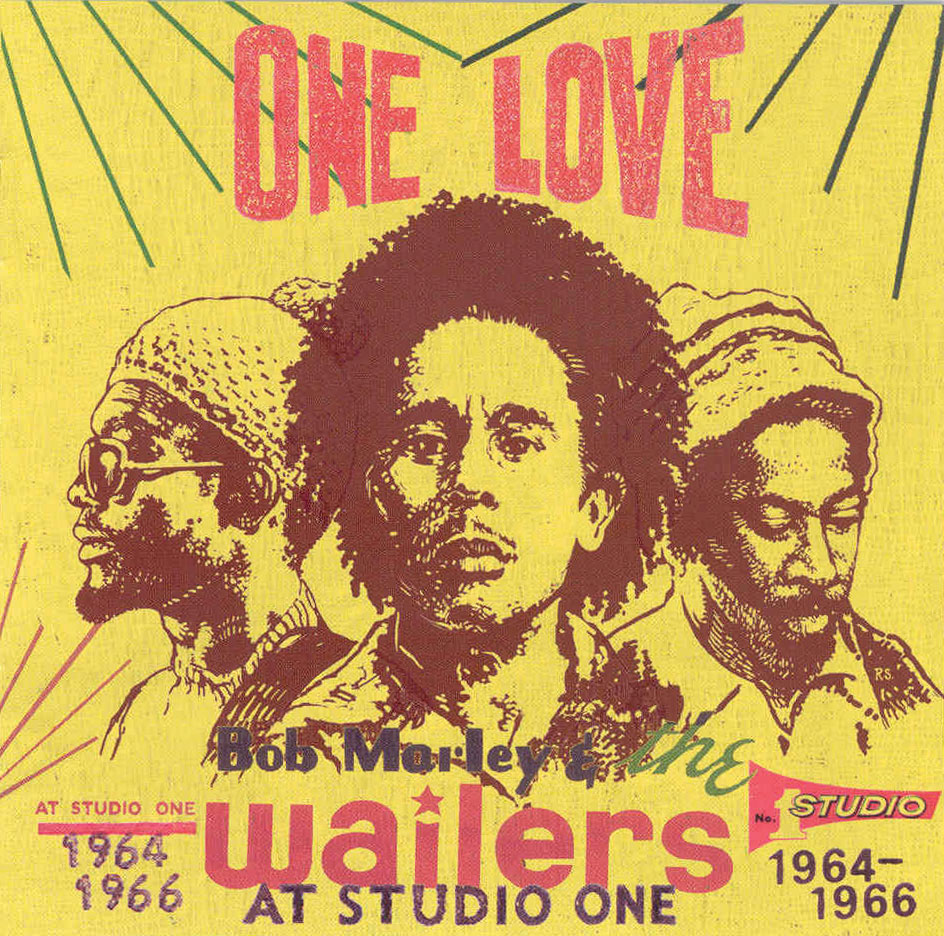

Despite the short-lived burst of postwar optimism and national pride that ensued, hundreds of thousands of Jamaican immigrants in search of new opportunity — my father included— flooded into the great imperial cities, London and New York, from which the island’s plantation economy continued, in large part, to be overseen. It was also by way of these immigrants that the sounds of Jamaican music, produced from the poverty and culturally syncretic creativity of the sprawling shantytowns of Jamaica’s capital city, began to percolate through England and the United States in the 1970s. By the time of his death in 1981, Bob Marley, perhaps the greatest visionary of this musical movement, was not only an internationally recognized pop singer, but also a symbol of Black Power and Third World liberation the world over. Musicality and leonine looks may have elevated him to stardom, but it was Marley’s pedagogical gift that ensured his status as a significant figure. The tropicality of The Wailers’ music was anchored by its historical weight, grounded in a critical consciousness that located Jamaica’s present-day poverty in centuries of slavery, colonial (mis)education, and raw economic exploitation. Marley’s lesson was clear to me even as a child; the movement of the phonograph needle across a record like “Slave Driver” (1973) brings the past and the present together into haunting conjunction. The song’s insights into the psychological distortions of colonialism are matched by the rhythmic intensity and low frequency heft of its sound:

Every time I hear the crack of a whip

My blood runs cold

I remember on the slave ship

How they brutalized our very souls

(Oh God have mercy on our souls)

Today they say that we are free

Only to be chained in poverty

Good God, I think it’s illiteracy

It’s only a machine that make money

Slave Driver, the table is turned…

Catch your fire, so that you can get burned

An historical tableau-vivant of slave ships and sugarcane fields, Marley’s song seems to echo Frantz Fanon’s characterization of the Caribbean as a “becalmed zone,” an “unchanging dream” in which the requisition of raw materials and the exploitation of native labor remains the only historical constant. This is the “every time” of the first line of the lyric, a recurrent event or persistent memory, neither singular nor safely in the past. In the face of repetition, Marley’s song folds two historical moments into one with “the crack of a whip,” allowing us to hear our way into history, to prise open an audible passageway between collective memory and the urgent poverty of the present tense.

At the same time, The Wailers’ art compels in us a certain cold-blooded analytical distance, doesn't allow us to get too comfortable or wholly inhabit its affective world. This is a popular song, but also a kind of miniature epic. The “slave driver” is a stand-in for history, addressed by way of apostrophe, an imagined off-stage presence who is not really present and cannot talk back; and Marley himself ‘plays’ an archetypal role as well — the defiant slave, the mutineer, the maroon. In the introductory statement of the melody, and with each further invocation of this figure, Bunny Livingstone and Peter Tosh of The Wailers provide a cool, melancholy harmonic counterpoint, shading Marley’s impassioned lead. This harmonic undertow, so different in tone from the American doo-wop and jump blues records through which The Wailers and other Jamaican vocal trios learned their trade, descends in tandem with the bass line with all the inevitability of a gravitational pull. There’s no uplift here, no promise of release, no unambiguous turning of the tables. For the “brutality” Marley confronts is not merely that of the slave driver, but of the song itself. The drama it stages—a fantasy of violent retribution, of revenge—is as much a product of the moral economy of slavery as the slave-driver himself. Thus the song’s most poignant and self-reflexive moment comes as a painful interjection, at once afterthought, apostrophe, and plea, a surplus line sticking out like sore thumb from the otherwise tightly wound fist of the first verse: “Oh God have mercy on our souls.” Anger is a necessity, an essential adjunct of any attempt to memorialize the past and salvage the future. Yet it’s also part and parcel of that past, a psychological brand and a form of brutalization. That’s why “Slave Driver” keeps its cool, maintaining a measured and critical distance from its own vengeful energies, alchemically transforming raw anger into historical awareness, and raw affect into a kind of affective history of slavery in the Caribbean. The Wailers, long notorious as “rude bwoys” and “stepping razors” in the urban slums of Trenchtown, turn out to have more than a little affinity with Mack the Knife.

Andrew F. Jones is Professor of East Asian Languages and Cultures at UC Berkeley. He is participating in the study group on Music and Sound at the Townsend Center.

This article can be found in the February/March 2013 newsletter.