Visions from the Peripheries

Figure 1: Outer of two windows for passing

supplies into a dark retreat. Terdrom, Tibet.

"By breaking with the objectivity which fascinates waking consciousness and by reinstating the human subject in its radical freedom, the dream discloses paradoxically the movement of freedom toward the world, the point of origin from which freedom makes itself world" (Michel Foucault, Dream and Existence).

Across the humanities, much attention has been directed to the marginal. From the margins of philosophy, to marginal voices and border regions, many have sought to open our eyes, our ears, and our language to what lies hidden at the periphery, just outside our field of view, just beyond our hearing, in a language we cannot quite make out. Each day is bracketed by sleep, our waking lives by the liminal realm of the dream. A study of dreaming therefore leads us into a fundamentally peripheral world, one defined by solitude, contemplation, and ulterior visions. In Tibet, practitioners of the Great Perfection, or Dzogchen, explore all these themes by undertaking a “dark retreat.” Early European visitors to Tibet imagined that monks were being buried alive, and indeed Tibetans themselves view the dark retreat as a means to simulate the processes of sleeping and dying. They also see it as an opportunity to explore the peripheries of consciousness and thus, they say, to reveal a point of origin where the natural freedom of the imagination is expressed.

The typical Tibetan dark retreat lasts for seven weeks. It does not take long for its practitioners to begin perceiving incessantly changing cloud-like displays, vague forms that come and go in the darkness. As one thirteenth-century author recounts, “The visions tumble like water falling down a cliff face, or like mercury scattering and beading together. They are unstable, arising and ceasing, scattering and regathering, shaking and quivering. Inwardly, one’s experience of concentration is weak and fleeting, and as the visions wax and wane, doubts arise.” These shifting visions and the practitioners’ own unstable mental state develop, in other words, as symbiotic reflections of one another. As the shapes drift and shake, the eyes chase after them, struggling in vain to focus on anything at all and becoming ever more agitated. As they grow strained and even ache unbearably, the practitioner’s drive to fix objective appearances is revealed as a habit deeply inscribed within not just her psyche, but the very musculature of her eyes. Buddhist scriptures frequently condemn the dualistic polarizations of subject and object that characterize our ordinary patterns of ego-logical thinking. With her eyes now deprived of their desired objects, the dark retreatant begins to experience these habitual reifications not just as some abstract doctrinal notion, but as a strong physical compulsion. After some days, however, the “oceans” of one’s eyes are said to relax. As they give in to the darkness, they grow more concentrated, and the disturbing images begin to subside. Once this happens, far more distinct, luminous visions are said to emerge. Unlike the earlier scattered shapes, these vivid new apparitions appear and disappear all at once. Peacock feather-like displays, faces, and even landscapes—all brightly colored—appear vividly real and emerge spontaneously, without any willful effort on the practitioner’s part. Tibetan texts insist that these dramatic displays are self-organizing and that they will continue to form as long as the practitioner maintains an open and non-appropriating gaze. One will see, in other words, as long as one does not look.

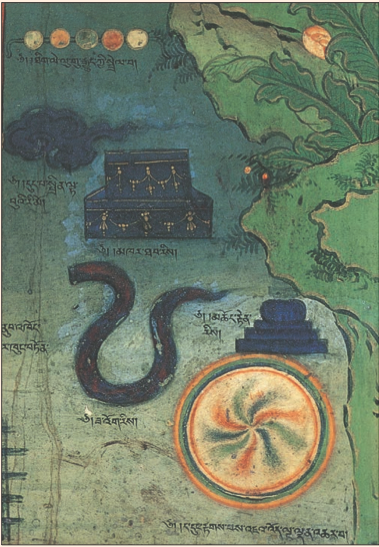

Figure 2: Abstract visions of the

Great Perfection meditator.

Lukhang murals, Lhasa.

Similar visions may also be elicited, Great Perfection texts explain, by gazing openly into the sky or at light-rays for extended periods. Doing so, the practitioner soon notices what are termed “linked chains of lambs,” series of small translucent circles attached by short strings: “fluttering and undulating vajra chains... endowed with countless little circles like pearls on a string.” One might recognize in these chains the far more mundane occurrences known by the modern medical establishment as “floaters”—tiny clumps of gel within the eye vitreous. Many readers will have seen these translucent “objects” (that are part of the eye and thus, quite literally, also subject) and the way they slide out of one’s vision as one tries to look at them. In fact, this frustrating elusiveness is precisely what makes them such effective objects of meditation. In the words of one text, “the linked chains of awareness must be divested of their constant movements of entering and receding from [the field of vision], whereby they come to be embraced within the sky.” The initial aim of sky gazing, then, is to bring these fluctuating chains, or floaters, to rest—again, to see them without looking. As in the dark retreat, as the practitioner’s gaze opens, an assortment of further visual experiences are said to emerge: lattice patterns, small spheres surrounded by concentric circular rainbows, patches of dark blue light.

Whether they emerge out of the darkness of the dark retreat or the light-rays of the sun, such vivid apparitions are radically different from ordinary visual images that appear to be independent of the observer: They transcend the dualisms of subject and object. The practitioner sees them before her, yet only as long as she does not objectify them and remains aware of them as projections of her own mind. For this reason, one eighteenth-century master of the Great Perfection advises: “They are merely reflections of the radiance of awareness arising externally. Therefore do not fixate on them as absolutely real.” In such statements the tradition recognizes them to be projections of the practitioner’s own mind. (Whether they are wrought by unconscious neurophysical memory or by karmic imprints depends on one’s perspective.) And in this they share much in common with dreams. Every night when we dream, the darkness opens us to the same kind of non-dual visions that are at once object and subject.

Figure 3: Practitioner of dream yoga.

Lukhang murals, Tibet.

Modern methods of dream interpretation developed in Austria and Switzerland a hundred years ago. Psychoanalysts are drawn to the dream for its poetic paradoxes and multivalent truths, and they treat the dream as a window onto an unconscious world untrammeled by concerns of the superego. By interpreting the dream, the analyst thus looks through its visions to a world of truth and repressed memories. The development of such techniques involved a remarkable turn toward the peripheral world of the dream.

A different approach to dreaming developed in India and Tibet a thousand years ago. Through the practice of dream yoga, Buddhists learn to dream lucidly, to be aware of the dream as dream while remaining within it, without waking up. The lucid dreamer cultivates a delicate relation to appearances: If too much attention is given to the objects of the dream, their non-dual nature will be forgotten, and the dreamer will no longer be lucid. If too much weight is placed on the subject, the practitioner will wake up into the world of ordinary objectivity. But by balancing between these two extremes, she frees the dream to unfold, suspended between subject and object, between objective vision and no vision at all. This lucid state of suspension also belongs to the practitioners of the dark retreat and to the Great Perfection sky gazers, who see without looking, who loosen engrained habits of seeing and learn to dream while awake.

The poetic imaginings of the dream may seem nothing more than that—poetry. The philosopher Owen Flanagan has even suggested dreams may be evolutionary side effects, useless “free-riders,” the spandrels of consciousness. Despite the dream’s marginal place in our lives, however, it is through its very insignificance, its transcendence of subject and object, that it has the potential to be radically revealing. As the Great Perfection practitioner breaks from the objectifications of waking consciousness, she is said to discover the very root of consciousness, where liberation expresses itself as imagination.

Jacob Dalton is Assistant Professor of Tibetan Buddhist Studies in the departments of South and Southeast Asian Studies and East Asian Languages and Cultures. His current book project is on manuscript culture and the role of ritual manuals in the development of early tantric Buddhism.

This article can be found in the September/October 2012 newsletter.